Thanks very much for coming today, and thank you to the organizers of this conference – the Haskayne School of Business and the C.D. Howe Institute – for putting together an impressive forum where we can discuss what I would argue is one of the defining public policy issues of our time.

These types of conferences, of course, tend to attract the most obsessive of policy wonks: People who can quote, by heart, obscure subsections of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act; People who think that the Pan-Canadian Framework for the Assessment and Recognition of Foreign Qualifications is great cocktail-party small talk; People who not only know that FOSS and PRRA and LINC and SPOs are not obsolete Middle English words, but who can also tell you exactly what those acronyms mean.

In other words: My kind of people.

I have been the Minister of Citizenship, Immigration and Multiculturalism since the fall of 2008, and of course, an obsessive interest in all aspects of the immigration system is part of the job description.

But I also came into the job with a conviction that has only grown stronger over the 44 months I have served as Minister.

My conviction is this: We have no choice but to succeed as a country in meeting our many immigration challenges. Our success in this area is central to the future of our economy, to the future strength of our society, and indeed, to the future of our nation.

This conviction drives everything we do at Citizenship and Immigration Canada. And I know it has resonance among the population of this country.

I am always reassured and impressed by something that consistently shows up in public opinion polls: Despite any disagreements Canadians may have on individual policies, we share a broad consensus that immigration is an unambiguously positive force in our country.

That broad pro-immigration consensus exists across political, demographic and regional lines. It is also reflected in our national politics: We don’t have a mainstream anti-immigrant political party, for example, which is not the case for many other democratic, industrialized countries.

Of course, this makes my job just a little bit easier than that of many of my counterparts across the democratic world. When I travel to other countries, or speak with international counterparts, I frequently note the wrenching, existential debates over immigration that exist in many places – debates that can be quite disruptive to civic harmony and to economic prosperity in those societies.

Here in Canada, for a great variety of reasons – historical, geographical, cultural, economic – we have largely escaped this discord, and that has been to our great advantage as a society.

Along the same lines, I am glad to see that there has been increasing international recognition of our successful Canadian approach to immigration and multiculturalism.

Just a couple of weeks ago, CNN aired a short documentary on what it saw as weaknesses in the American immigration system.

One part of the documentary highlighted Canada’s immigration successes. In fact, the documentary specifically focused on Calgary as a great international example of a city leading the way on immigration and multiculturalism. Mayor Nenshi and other Calgarians appeared in the item, offering insights based on their personal experiences in this great city.

In the documentary, CNN host Fareed Zakaria described Canada as a “place that’s getting it right.” He went to say – and I quote – that:

“Canada (is) a nation that now has the most successful set of immigration policies in the world... Canada's economy is thriving because it actively seeks immigrants to fill labour gaps and then grants those immigrants the full benefits and opportunities of being Canadian.”

So it’s clear that the world is beginning to notice our successes in the area of immigration policy.

Rationale

I’d like to take the opportunity today to talk to you in some detail about our policies.

In the last few years we have implemented many positive reforms to Canada’s immigration system – reforms that have begun to change the system to better serve immigrants, and to better serve Canada.

But, of course, we have more to do to get to where we need to be.

In fact, I believe we have arrived at a point of transformational change to our immigration system.

The changes we are planning are long-needed and part of our commitment to ensure the immigration system is managed so as to maximize the benefits to Canada, as well as to new Canadians.

We will do so while sustaining our commitment to family reunification and refugee protection. In particular, we are maintaining one of the world’s largest refugee resettlement programs from overseas at a time when other countries are reducing theirs.

As we move forward with these changes, the Government has two broad but complementary goals:

First, we aim to foster an immigration system that can fill significant labour shortages across the country and help us meet our economic needs more quickly and efficiently: A system designed to give newcomers the best possible chance to succeed.

Secondly, as we move forward with these changes, we are implementing policies that safeguard the integrity and security of our immigration system.

I always like to stress the fact that the security and integrity of the immigration system go hand in hand with that system’s ability to best serve our society and our economy.

A balanced approach is key. Improvements in efficiency, effectiveness and economic outcomes must be balanced with policies that ensure the integrity and security of the immigration system.

The New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman wrote a great column about this very topic a few years ago. He used a metaphor that probably makes more sense in his American context, saying the ideal immigration system is “a very high fence, with a very big gate.”

You could use a different metaphor – for instance, a large, welcoming open door supported by solid walls. The point remains the same. Gates don’t exist without fences. Doors don’t exist without supporting walls. In other words, you can’t have a an immigration system that quickly and efficiently welcomes in the people we need in Canada without having secure mechanisms in place to keep out those who are not welcome within our borders.

In fact, if you don’t ensure the integrity of the immigration system, then you are likely to provoke the kinds of wrenching, existential and divisive debates about immigration that I described a few minutes ago – debates that call the whole system into question.

In his column, Friedman argued that when the system has integrity, it makes the population at large more secure about immigration “and able to think through this issue more calmly.”

So by developing laws, policies, and practices that make our immigration system more secure, we ensure continuing support for immigration, which in turn allows us to maintain the open, generous approach to immigration which has served our country so well throughout our history.

Safeguarding the Integrity of the Immigration System

In that spirit, the Government has taken a number of recent initiatives aimed at safeguarding the integrity of our immigration system.

Protecting Canada’s Immigration System Act

The Protecting Canada’s Immigration System Act is probably the most prominent recent example of our efforts in this regard. We introduced the Bill a few months ago and I am very proud to say that we expect it to gain Royal Assent later today.

This is a notable and worthy development. With the imminent passage of this legislation, Canadians will benefit from long-needed reforms to the asylum system – reforms that will help deliver faster decisions on refugee claims, and deter abuse.

At the same time, we will now be able to offer more timely protection to those refugees who truly need it.

Also, Canada’s efforts to deter and to combat the scourge of human smuggling will be bolstered.

And we will also be able to introduce biometric technology for the mandatory screening of temporary resident applicants. This will help prevent known criminals and failed claimants from abusing the immigration system.

So, this is indeed a historic day in the history of Canada’s immigration system, a day that will see the system become more secure.

Faster Removal of Foreign Criminals

We took another important initiative just last week when we introduced in Parliament the Faster Removal of Foreign Criminals Act. This Bill complements the Protecting Canada’s Immigration System Act in its efforts to help safeguard the integrity of the immigration system.

Under the current system, many foreign criminals have been able to appeal deportation orders and extend their time in Canada following convictions – often by many years.

We are talking here about murderers, drug traffickers, fraudsters, child abusers and thieves, some of whom are on most-wanted lists.

The measures in this Bill will help stop this revolving door of multiple appeals by non-citizens who are found to be inadmissible to Canada.

Other Integrity Measures

Other initiatives we are undertaking include combating marriage fraud, better regulating the immigration consulting business, and tackling immigration fraud by cracking down on unscrupulous individuals who try to cheat the system.

Marriages of convenience are used by some as a quick and easy route to Canada for fraudsters who never intended to stay with their spouse or partner.

Tragically, in many of these cases, the Canadian spouse is duped into marriage fraud, and may suffer great personal distress when the fraud becomes apparent. Others are complicit in the plot.

We are bringing in new measures that will combat this abuse of our immigration system by deterring foreign nationals from entering into a marriage of convenience to gain permanent status in Canada.

Similarly, we are taking aggressive action against those who perpetuate visa scams and application fraud, including unauthorized representatives who provide advice or representation for a fee at any stage of an immigration application or proceeding.

Together, these initiatives and others help us to safeguard the integrity and security of the immigration system.

Transformational Change

Again, one of the most important reasons for focusing on the integrity of the system is because if we neglect these issues – the “very high fence” issues – we will not have the flexibility or the public support to maintain our “very big gate”.

And we have very big plans for that very big gate.

We are making transformational changes to the immigration system so that it better serves our economy and our society.

We envision a “just in time” system, in which the entire process for a skilled immigrant to apply to come to this country, and then to be accepted and admitted to Canada, and gainfully employed here, takes only a few months instead of many years.

Reforms we have undertaken over the past few years have helped to reduce backlogs, reverse wait times, gain better control of intake, crack down on fraud and abuse of the system, and improve the timeliness of the services we provide.

These reforms have better focused our immigration system on fuelling Canada’s economic prosperity.

But there is still more work to be done to put into effect an efficient “just in time” system that best meets Canada’s economic needs.

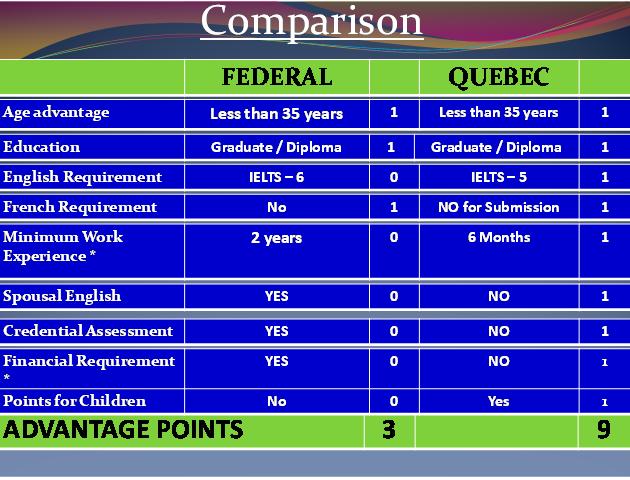

Federal Skilled Worker Program

Pre-2008 FSW Backlog Elimination

As many of you know, our main economic immigration program has traditionally been the Federal Skilled Worker Program. In fact, more immigrants still come to Canada through this program than through any other.

For the immigration system in general – but especially for the Federal Skilled Worker program – one of the greatest challenges comes from the large backlogs of applications that have accumulated in the system.

Even with measures we took in 2008 to reduce the backlog in the Federal Skilled Workers program, we still have a backlog of nearly 300,000 people, and wait times of several years, rather than months.

Measures proposed in our Economic Action Plan 2012 will help align the system more closely with our economic needs.

They will enable Canada to eliminate the large backlog of old federal skilled worker applications that is gumming up our immigration system.

We are closing the applications and returning fees to all affected individuals.

By moving quickly to eliminate this longstanding backlog, we will be able to shift our processing priority towards newer federal skilled worker applicants who have the current, in-demand skills that our economy needs.

This will, I believe, transform the system.

Creation of a Pool of Skilled Workers

In recent years, New Zealand and Australia – countries with immigration systems similar to ours – have made their systems nimbler, more flexible and more responsive to modern labour-market realities.

Like us, New Zealand legislated an end to its backlog in 2003 and put in place a system where prospective applicants can be selected from a pool made up of prospective immigrants with the skills, experience and education that are most needed in that country. Australia is introducing a similar system this year.

Rather than having to process all applications, regardless of whether an applicant’s skills match current labour market needs, their resources can now be put towards actively matching the best recently qualified applicants to current economic needs and even to specific companies, who can use the pool of applicants as a pool of prospective recruits.

We want to explore with provinces, territories and employers approaches to developing a similar pool of skilled workers who are ready to begin employment in Canada.

The goal is a simplified and expedited immigration process that selects the applicants with the best and most in-demand qualifications and, at the same time, eliminates the scourge of backlogs, which, as we have seen, can bring an immigration system nearly to a standstill.

FSWP Points System

As we explore options for a more significant overhaul of the applications system in the coming years, we are already taking steps to improve our economic immigration system in other ways.

We are currently working to improve the points system for our Federal Skilled Worker program to bring it more in line with the needs of our modern economy.

In 2010, we completed an extensive evaluation of the FSW program which suggested that overall it is working well and selecting immigrants who perform well economically.

It also showed that selecting applicants based on human capital criteria has led to dramatically improved outcomes.

“Human capital criteria” is one of those terms that experts love to throw about because it sounds clever and cutting edge. Really, it’s an unfortunately impersonal bit of jargon for very important, very personal attributes.

Here is one example: Official language proficiency. The data clearly show that skilled immigrants who speak French or English well will be more successful in the Canadian job market.

Beyond this, another strong indicator of success is pre-arranged employment. Skilled workers do better if they immigrate to Canada with a job offer in hand.

So we need to simplify the process for employers to hire the skilled workers they need and to get them here sooner.

Based in part on our extensive data on outcomes for skilled workers, and also on recently-completed public consultations, we will propose changes in coming weeks to the selection criteria that will include more emphasis on language ability, youth, arranged employment, and other factors that experience has shown are good predictors of success.

Our goal is to have a better FSW program in place by the end of this year.

Skilled Trades

Another notable change is coming to the FSW program.

We will create, for the first time, a separate stream for skilled tradespersons, which will allow these applicants to be assessed based on criteria geared to the reality of their specific qualifications rather than false hopes, putting more emphasis on practical training and work experience rather than formal education.

I am talking about workers in construction, transportation, manufacturing and service industries that are in high demand in Canada, particularly in the natural resources and construction sectors.

During our consultations last year on improving the Federal Skilled Worker Program, stakeholders agreed that changes were necessary to make the program more accessible to tradespersons, who have traditionally been disadvantaged due to criteria in the points grid that is better suited to professionals.

So we are taking concrete steps to do a better job of welcoming skilled tradespersons to the country.

Other Immigration Programs

Provincial Nominees

While the Federal Skilled Worker Program is still our largest economic immigration program, in recent years, provinces and territories have begun to play a much bigger role in selecting economic immigrants under the Provincial Nominee Programs.

The PNP has, in fact, grown over the past decade to become the second-largest economic immigration program

Here in Alberta, for example, the Provincial Nominee Program has grown more than 2,500 per cent in just a few years.

The program brought in 482 people to this province in 2003 – that number includes nominees and their dependents. That represents only one per cent of total immigration to Alberta that year.

In 2010 – just a few years later – the program brought in 12,715 immigrants, representing 23 per cent of total immigration to Alberta that year.

The expansion of the PNP has also brought about a better distribution of newcomers across the country.

The majority of newcomers used to settle in Toronto, Montreal and Vancouver, even though strong job opportunities were available in other regions.

Thanks in large part to the PNP, 37 per cent of all economic immigrants in 2009 intended to settle in cities outside of the “Big Three.” Immigration to the Prairie Provinces has tripled and, in Atlantic Canada, it has doubled.

So, not only has this program been good for regional economic development, but I would argue that it has been an exercise in nation-building, expanding the benefits of immigration to every corner of Canada.

While we consider the overall program to be a success, there is room for improvement. A recent evaluation of the PNP recommended that we establish minimum language standards for all provincial nominees.

So as of next week, provincial nominee applicants in semi- and low-skilled professions will have to undergo mandatory language testing and achieve basic proficiency in comprehension, speaking, reading and writing.

At the same time, the Government will work with the provinces and territories to better focus the PNP on direct economic and regional labour market needs and to eliminate overlap and duplication between the federal and provincial programs, including family reunification, investment, and student streams.

Canadian Experience Class

Our newest economic immigration program is called the Canadian Experience Class. It is a personal favourite of mine, and it’s already had quite a bit of success since we introduced it in 2008. I wish we had started it even earlier.

In the past, when foreign students came to this country to study, we would tell them something along these lines once they earned Canadian degrees:

“Congratulations, you now have a degree that will be recognized by a Canadian employer, you have perfected your English or French language skills, now please leave the country and if you want to immigrate, get in the back of an eight-year long queue and we’ll be back in touch with you.”

How shortsighted could we be?

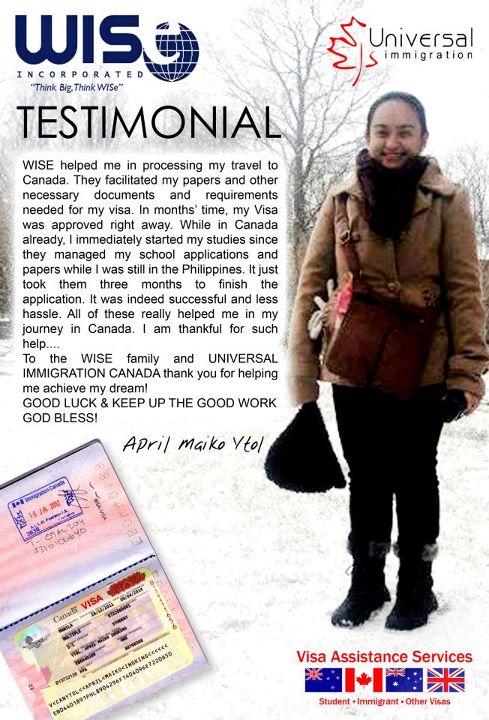

Now, we have the Canadian Experience Class, which allows temporary foreign workers and international students with skilled work experience and/or education in Canada to apply for permanent residence.

The CEC is an effective program because applicants already have valuable Canadian work experience, and often Canadian diplomas and degrees that will be immediately recognized by Canadian employers. In many cases, they already have a job lined up. In short, they are set for success.

So now, we say something different to these applicants. We say:

“Okay, you’ve graduated from a Canadian university or college, and by the way, we’ve given you an open work permit for two years. If you work for an employer for one year following the diploma or the degree, we are going to invite you to stay as a permanent resident, on a fast track basis, because you are set for success. You’re already pre-integrated, you got the degree that will be recognized by a Canadian employer, you’ve already got a job, and your English language skills or French language skills are perfected.”

The program has been growing quickly since it was introduced, with admissions increasing from about 2,500 new permanent residents in 2009 to more than 6,000 last year. Even more are expected in 2012.

Currently, to be eligible to apply, applicants under the temporary foreign worker stream of the CEC must have 24 months of full-time work experience in Canada within the last 36 months.

Under new proposed regulatory changes, however, we will be reducing the requirement to 12 months of Canadian work experience.

Immigrant Investor Program

Another immigration program we will be improving is the Immigrant Investor Program, or the IIP. Our goal in this regard is to best determine how we can encourage more active foreign investments in the Canadian economy.

Let me be blunt about this particular program: It’s broken. In trying to encourage more active foreign investments in the Canadian economy, the existing IIP falls short and it undervalues Canada.

When you compare our Investor Program to those in Australia, New Zealand and the United States, you see that they require an active and durable investment in their economies, which we do not.

We need an investor program that brings in real capital, to ensure we have long-term growth in jobs and the economy.

Instead of just lending money to provinces and territories for five years, we will explore ways in which to attract immigrants who want to invest in Canada’s future by making significant investments in private sector innovation and growth.

Federal Entrepreneur Program

We also hope to tap into the entrepreneurial spirit that so many immigrants seem to have by developing new approaches for a Federal Entrepreneur Program.

Last summer, we implemented a temporary moratorium on applications. This was another example of a program that was plagued with a large backlog –and with unacceptable processing times of 5 to 6 years. In addition, the criteria for inclusion in the program tended to favour small, safe business ventures rather than innovative or entrepreneurial ideas.

So we consulted with industry associations on how to develop a program for innovative entrepreneurs that will bring the best and brightest entrepreneurial talent we can to Canada.

The idea is to proactively target a new type of immigrant entrepreneur, people who have the potential to build companies that can compete on a global scale and create jobs for Canadians. In the race for global talent, countries that do not open themselves up to highly mobile entrepreneurs will quickly fall behind economically.

We will not stand by and let Canada miss out as creative minds look for a place to locate their start-up businesses. We want to send a clear message that Canada wants them, their talent, their ideas, and their businesses.

Foreign Credential Recognition

One issue that touches economic immigrants across all of our different programs, and one I hear about everywhere I travel, is Foreign Credential Recognition.

We need to correct the common situation where skilled immigrants come to Canada only to discover too late that their credentials aren’t recognized here or require significant investments of time and money to be brought up to Canadian standards.

So, among other measures, we propose moving to a mandatory assessment of foreign educational credentials as part of the selection process for Federal Skilled Worker Program applicants.

This means that, before we accept them, applicants would be required to have their educational credentials assessed by a designated and qualified third party to determine their value in Canada.

They would then only receive credit for their qualifications if they are equal to Canadian qualifications.

Our goal with this change is to better select immigrants, so they can hit the ground running once they arrive by integrating quickly into our labour market.

Temporary Foreign Workers

I should also mention a recent initiative that I think is of particular interest in this province, given the great need for Temporary Foreign Workers in Alberta, particularly in the energy and resource industries.

According to the Alberta government’s own estimates, there will be a cumulative shortage of more than 114,000 workers here by the year 2021. That poses a major challenge to not only the Alberta economy, but also the Canadian economy, given Alberta’s important national role.

In response to labour shortages here and in other parts of the country, we plan to realign the Temporary Foreign Worker Program so that it better meets labour market demands and supports the economic recovery.

This will dramatically improve service to employers in need of workers.

While employers will have to continue to demonstrate that they have made all reasonable efforts to recruit from the domestic labour force, the Government recently launched a new streamlined approach for speeding up the process for hiring temporary foreign workers to fill short-term skilled labour needs.

This new approach – called the Accelerated-Labour Market Opinion or A-LMO – will reduce the paper burden on employers, allow LMOs to be issued within ten business days, and strengthen protections for foreign workers through employer compliance reviews, resulting in a more secure working environment for these workers.

Previously, LMOs took, on average, 22 business days to process. But that’s a national average and we know that employers in Western provinces tended to experience even worse delays due to the high volume of applications received.

Parents and Grandparents Program

I’ve mentioned backlogs in the context of our economic immigration programs, but they have also been a problem in what we call our “Family Class.”

Perhaps the best-known of our Family Class immigration streams is the Parents and Grandparents Program, which allows Canadian citizens and permanent residents to sponsor their parents and grandparents from abroad.

As of last year, this program suffered a huge and growing backlog of 165,000 applicants, with processing times of seven years.

As well, there have been questions raised about the sustainability of this program, its effectiveness in reuniting families in a timely manner, and the economic burden it places on provincial health care systems.

In the 30 years between 1980 and 2010, about 275,000 senior citizens arrived in Canada through this program. The annual health care cost for them is estimated to be about $10,742 dollars per person. That comes to about $3-billion dollars a year.

We began to take action on this last fall, when we announced the first phase of the Action Plan for Faster Family Reunification. It included an increase of about 40% in the number of sponsored parents and grandparents that Canada will admit year in order to help clear the backlog.

At the same time, we initiated a temporary pause of up to 24 months on the acceptance of new applications, to give us time to redesign the program.

We also introduced a parent and grandparent multiple-entry Super Visa, which is valid for up to 2 years. This enables parents and grandparents living overseas to visit Canada as many times as they want without placing an undue burden on Canada’s generous health care system and other social benefits.

We plan to have a new and sustainable Parents and Grandparents Program by the fall of 2013.

Our redesigned program will be designed to avoid the problem of future backlogs, while being sensitive to fiscal constraints, bearing in mind Canada’s generous health care system and other social benefits. It will be a program that is fair to all Canadians.

One Last Thing...

I have tried to take the time today to outline a number of the transformational changes we plan to make to the immigration system, as well as those we are in the process of making.

But before I wrap up, I have one last thing to announce. In fact, I am going to give you a bit of breaking news here today that has bearing on a couple of the immigration programs I have discussed with you.

As another important step toward the transformation of Canada’s immigration system, I am announcing today that we will be hitting the reset button on the Federal Skilled Worker Program, our main economic immigration program.

Effective next week, we will be issuing a temporary pause on new applications to the FSWP.

This is a way to ensure that improvements to the program have time to be put in place, which will give new applicants the opportunity to be even better positioned to succeed in Canada.

I mentioned these changes earlier: A significantly reduced backlog of applications, a revised points grid, and a skilled trades program.

We expect to re-open intake on new applications on January 1, 2013, without the burden of a large backlog to divert us, and with the improved points grid and new skilled trades program in place.

I should note that this pause will have no effect on FSWP admissions, as we have more than enough applications in our inventory to continue to welcome thousands of skilled workers each year.

As well, the pause won’t affect applicants who have job offers in hand from Canadian employers.

At the same time, beginning next week, we will also be issuing a temporary pause on new applications to the Federal Immigrant Investor Program. This will allow us to work through our existing inventory of applications as we continue to consult on reforming the program.

Conclusion

I am glad to have had the opportunity today to talk with you about some of the transformational changes we are planning for our immigration system, including the breaking news you just heard.

As we have embarked on these changes, we have been happy to see that many Canadians – stakeholders, media commentators, and also ordinary Canadians – have shown public support and enthusiasm for what we are trying to do.

Of course, many of you here today are employers, and you know better than anyone how important it is for our rapidly changing economy that our immigration system remains responsive to our labour market needs.

You have a role to play in the ongoing process of ensuring that it does, and we welcome your involvement.

I am always eager to consult with those who have first-hand knowledge of the economic impacts of our immigration policies. I am always pleased to see employers who are actively engaged in integrating skilled workers into Canadian society.

Together, we need to ensure that the immigration system is responsive to employers needs.

To some extent, as the Government continues to work on making these changes, the ball will end up in the court of employers. It’s up to employers to use the tools of a transformed immigration system to bring in skilled employees to Canada. Indeed, a transformed system will only meet its potential if employers take advantage of it.

This is a partnership. Together with those who employ skilled immigrants, the Government of Canada recognizes the importance of immigration to our economic health and values the contribution of skilled immigrants who add to our international competitiveness.

We are all committed to facilitating the arrival of the best and the brightest to our country – now and in the future.

Canada needs a system that recruits people with the right skills to meet labour market needs in every part of the country, that fast- tracks their applications, and that gets them working in Canada as quickly as possible.

Because I’ve talked to thousands upon thousands of newcomers to Canada, and I can tell you with absolute conviction that that is what new Canadians want. And it’s what Canada needs. Thank you very much.

Chandigarh:

Chandigarh:

Philippines:

Philippines:

Canada:

Canada:

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

(With school Girls in Kerala)

(With school Girls in Kerala)

.jpg)

Immigration Minister Jason Kenney has earned both praise and criticism for changes to the way Canada handles economic immigrants. (CP file photo)

Immigration Minister Jason Kenney has earned both praise and criticism for changes to the way Canada handles economic immigrants. (CP file photo)

Dalhousie professor Jim McNiven, a former deputy minister of development in Nova Scotia. (Dalhousie University website)

Dalhousie professor Jim McNiven, a former deputy minister of development in Nova Scotia. (Dalhousie University website) Immigration Minister Jason Kenney, putting more emphasis on younger, blue-collar workers. (Canadian Press)

Immigration Minister Jason Kenney, putting more emphasis on younger, blue-collar workers. (Canadian Press).jpg)

There’s a big world waiting to be explored. Locally or globally, you can be the gateway to that world. In an industry where experience is everything, learn what it takes to deliver for the world’s travellers, passengers and guests.

By the end of the courseyou'll be equipped with the tools and techniques to find work in a wide range of hospitality, travel and tourism related roles including: Corporate Hospitality Associate, Corporate Travel Buyer, Hospitality/ Tourism Business Development Manager, Hotel / Tourism Account Manager, Project Manager – Planning, Tourism Destination Manager, Experience Manger, Hospitality or Tourism Relationship Manager, Hospitality /Tourism /Travel Sales Coordinator, and Marketing Assistant Manager among others.

There’s a big world waiting to be explored. Locally or globally, you can be the gateway to that world. In an industry where experience is everything, learn what it takes to deliver for the world’s travellers, passengers and guests.

By the end of the courseyou'll be equipped with the tools and techniques to find work in a wide range of hospitality, travel and tourism related roles including: Corporate Hospitality Associate, Corporate Travel Buyer, Hospitality/ Tourism Business Development Manager, Hotel / Tourism Account Manager, Project Manager – Planning, Tourism Destination Manager, Experience Manger, Hospitality or Tourism Relationship Manager, Hospitality /Tourism /Travel Sales Coordinator, and Marketing Assistant Manager among others. For some, wine is a pleasure to be enjoyed. For you, it’s that – and an exciting career! Join our award winning commercial teaching winery and ignite your passion for wine making. Whether you are a hobbyist and/or a wine enthusiast interested in enhancing your knowledge about wine, this program combines theoretical knowledge and skills with practical hands-on experience to quench your thirst.

For some, wine is a pleasure to be enjoyed. For you, it’s that – and an exciting career! Join our award winning commercial teaching winery and ignite your passion for wine making. Whether you are a hobbyist and/or a wine enthusiast interested in enhancing your knowledge about wine, this program combines theoretical knowledge and skills with practical hands-on experience to quench your thirst. In today's world, computers and electronics are at the core of almost everything we do. A course in Computer Engineering Technology prepares you to be a triple threat, able to work on circuitry, to write computer programs and to build computer networks, each of which is a job category of its own.

In today's world, computers and electronics are at the core of almost everything we do. A course in Computer Engineering Technology prepares you to be a triple threat, able to work on circuitry, to write computer programs and to build computer networks, each of which is a job category of its own. Course in this program puts you at the leading edge of aviation training. As a graduate of this program, you will be well positioned to compete in the global market as a professional pilot in general aviation and with regional air carriers, later progressing to corporate aviation and major airlines. The breadth and depth of the program mean that you could also pursue exciting careers in government regulatory agencies, airport authorities, flight test and evaluation, aircraft manufacture and marketing and the aviation insurance industry among many others.

Course in this program puts you at the leading edge of aviation training. As a graduate of this program, you will be well positioned to compete in the global market as a professional pilot in general aviation and with regional air carriers, later progressing to corporate aviation and major airlines. The breadth and depth of the program mean that you could also pursue exciting careers in government regulatory agencies, airport authorities, flight test and evaluation, aircraft manufacture and marketing and the aviation insurance industry among many others. As a student of Fashion Business, you'll be prepared to enter the fashion industry, one of the most exciting areas of business today. Course work will be delivered in a mixed mode of lab-based activities as well as theory-based formats that include guest lecturers from the industry.

As a student of Fashion Business, you'll be prepared to enter the fashion industry, one of the most exciting areas of business today. Course work will be delivered in a mixed mode of lab-based activities as well as theory-based formats that include guest lecturers from the industry. Event and Experiential Marketing is one of the fastest growing fields in marketing. It's about growing strong event brands and creating engaging experiences for target audiences. Event Marketing is a sophisticated discipline that involves both the 'marketing of events' as well as 'marketing through events.' Corporations and organizations integrate events into the traditional marketing mix as a means to connect consumers to their brands in a compelling way. Event Marketing is a strategic, disciplined approach to event planning and management, and involves sponsor brand activation and the amplification of live experiences through digital and social media.

Event and Experiential Marketing is one of the fastest growing fields in marketing. It's about growing strong event brands and creating engaging experiences for target audiences. Event Marketing is a sophisticated discipline that involves both the 'marketing of events' as well as 'marketing through events.' Corporations and organizations integrate events into the traditional marketing mix as a means to connect consumers to their brands in a compelling way. Event Marketing is a strategic, disciplined approach to event planning and management, and involves sponsor brand activation and the amplification of live experiences through digital and social media. The Behavioural Sciences diploma program gives you the opportunity to study the theory and clinical applications of the branch of applied psychology known as behavioural science. As a student in the Behavioural Sciences program, you will learn about Applied Behaviour Analysis (ABA), which is the science of understanding, analyzing and modifying human behaviour. As a student in this program, you will graduate with a deep understanding of the principles of Applied Behaviour Analysis (ABA) and the broad range of their possible applications.

The Behavioural Sciences diploma program gives you the opportunity to study the theory and clinical applications of the branch of applied psychology known as behavioural science. As a student in the Behavioural Sciences program, you will learn about Applied Behaviour Analysis (ABA), which is the science of understanding, analyzing and modifying human behaviour. As a student in this program, you will graduate with a deep understanding of the principles of Applied Behaviour Analysis (ABA) and the broad range of their possible applications. Brand Management involves understanding all aspects of a brand and then devising a plan in order to build brand equity. Brand Management is one of the major factors in any company's success. This program will focus on providing you with the skills and knowledge to develop and execute successful brand strategies in today's digital environment that are focused on consumers. As a graduate you'll be prepared for a wide range of rewarding careers.

Brand Management involves understanding all aspects of a brand and then devising a plan in order to build brand equity. Brand Management is one of the major factors in any company's success. This program will focus on providing you with the skills and knowledge to develop and execute successful brand strategies in today's digital environment that are focused on consumers. As a graduate you'll be prepared for a wide range of rewarding careers. Learn to sing, move and act. Acquire the performance and entrepreneurial skills to create a sensation. Hone your craft right in the heart of one of North America’s leading creative economies. There are programs available like

Learn to sing, move and act. Acquire the performance and entrepreneurial skills to create a sensation. Hone your craft right in the heart of one of North America’s leading creative economies. There are programs available like Advance the frontiers of science. Connect communities. Create technologies and environments. Discover a career where you can have a positive impact on our collective future. There are various programs available in different categories like:

Advance the frontiers of science. Connect communities. Create technologies and environments. Discover a career where you can have a positive impact on our collective future. There are various programs available in different categories like:

Meet every challenge, be open to change and realize your goals – whatever they may be. Excel in any business setting and succeed in organizations large, small or even your own.

Meet every challenge, be open to change and realize your goals – whatever they may be. Excel in any business setting and succeed in organizations large, small or even your own.  This program will focus on web and mobile app design and development, from concept to deployment. The program will encompass visual aesthetics (including typography, colour theory, and graphics), client and server programming, user experience design, and project management. Students will choose to enter the designer or developer stream of the program when they apply, although they can change their focus up until the third term.

This program will focus on web and mobile app design and development, from concept to deployment. The program will encompass visual aesthetics (including typography, colour theory, and graphics), client and server programming, user experience design, and project management. Students will choose to enter the designer or developer stream of the program when they apply, although they can change their focus up until the third term. There is no better feeling than saving lives... Studying medicine has been one of the most popular choices of bright and ambitious students. Let’s see what the advantages of studying Medicine are.

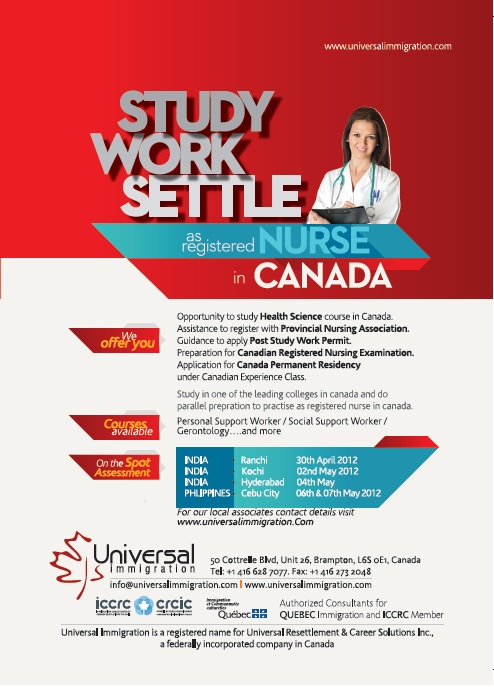

There is no better feeling than saving lives... Studying medicine has been one of the most popular choices of bright and ambitious students. Let’s see what the advantages of studying Medicine are.